I grew up hearing my father's stories of his adventures as a flyer and a fighter pilot in the Second World War.

As a kid I sat in rapt wonder at someone who actually did all those things I saw John Wayne doing in war movies,

and my wonder never abated over the years.

I present them here for your entertainment and enlightenment, as an example of one man's experience in

"The Big One." I've written them down as I remembered them, so any disagreement between the story

and anyone's knowledge of how things really were is probably the fault of me misremembering the story.

I always welcome new knowledge of the times and events, so if anyone out there reads something here that they know happened

differently, please feel free to contact me through the email listed on my home page.

And I'm always seeking photos of Dad's planes, since he never took any himself.

So if you find a picture of a P-47 that Dad may have flown (as described below), I'd appreciate a scan.

Enjoy...

|

A really poor scan of a very tiny wallet-size photo

of the Waco 10 in which Dad soloed in 1936. Click the pic to enlarge it. |

|

Aeronca C70, Franklin Lakes Airport. Dad knocked the wingtip off on a car when landing at night. Oops! Click the pic to enlarge it. |

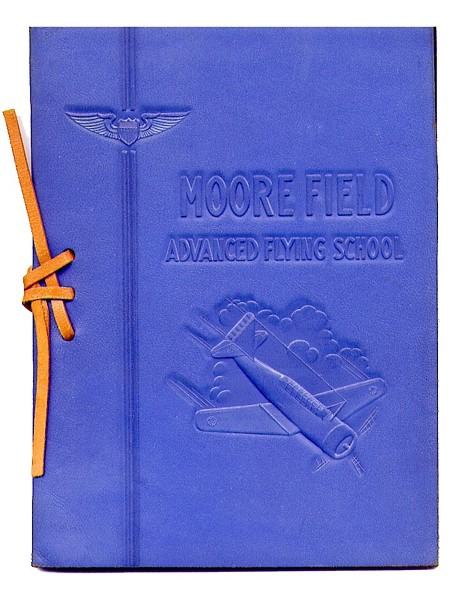

My father began his military training on Jan 28, 1943. He was stationed at Atlantic City, NJ, for three weeks of basic training, and then was sent to Butler university in Indianapolis for nine weeks of college (a pilot required certain courses). From there it was on to Kelly Field in San Antonio for classification. He qualified for pilot, navigator and bombardier and, naturally, chose pilot. Pre-flight training was at Kelly, and then he was sent to Moore Field, Corsicana, Texas, for primary training, where he soloed as an Army Air Force cadet on Sept 17, 1943. Basic flight training was up in Independence, Kansas, but advanced was back at Corsicana! Just like the Army! Good thing they had airplanes for all that traveling.

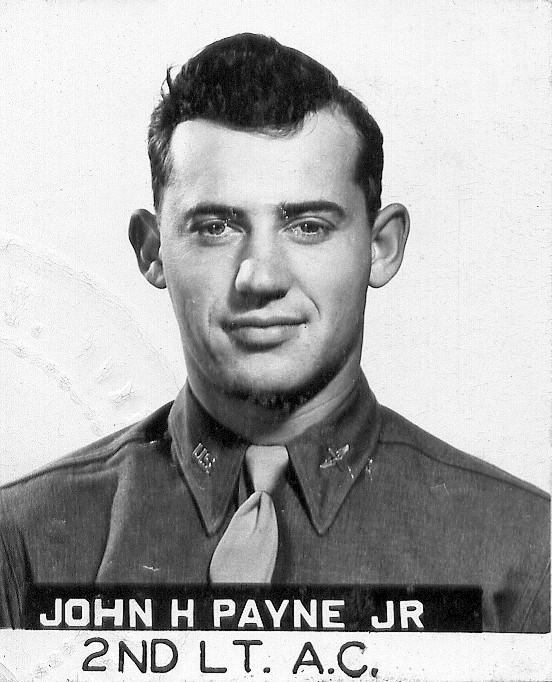

Graduating as a second lieutenant, he got his silver wings at Moore Field, Corsicana, Texas, with class 44-C, on Tuesday, March 12, 1944 at 11:00 AM.

My favorite story from training concerns an assignment to fly a new

lieutenant to another field. The Lt. was rather unpopular with the cadets, so Dad

thought he’d give the fella a “good ride.” Upon takeoff, Dad rolled the AT-6

inverted, and pushed the nose up to apply negative G and drive the man’s blood

into his brain.

This drew a warning call from the tower: “Be advised you are NOT

cleared for aerobatics on this flight!”

Dad replied that he understood, and went on to tell the tower who he

had on board.

The tower answered “Roger that, disregard previous transmission. Enjoy

your flight.”

Dad had the poor guy revisiting his lunch all over the rear cockpit in

short order.

One event that stuck in my father’s memory was a crash. He and an instructor were flying when another AT-6 crashed, killing the student and the instructor. Dad and his pilot flew over the wreck, and they saw two puffs of smoke rise out of the cockpit. Dad swears the two puffs rose straight up vertically, totally unaffected by the wind. His instructor flew up alongside the puffs and they followed them as high as they could, until the puffs rose out of sight. Now, Dad was never a very religious fella, but he always wondered about that. Smoke just doesn’t act like that. He saw a lot of people die over the next few years, but he never saw that phenomenon again.

After graduation Dad was stationed at Richmond Army Airfield, Virginia,

where he was introduced to the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt (affectionately known

as The Jug), and got ready to go to war.

For low-level practice the pilots were ordered to fly around the area

and stay below fifty feet. He tells me that he and his flight flew their P-47s

under every bridge on the James River. There was one bridge they weren’t too

sure about, though. It looked kind of low and narrow. So he and the fellas

drove out there with tape measures and surveyed the situation. The bridge

measured 14 feet above the water level, and well over 40 feet from bank to

bank. Well, that was plenty of room for a 40-foot-wide P-47 with a 12’ 6” prop,

wasn’t it? So four of them flew their Jugs screaming down the river at high

speed and buzzed under the bridge in train.

Oh, to have had a movie camera on that bridge!

While still stationed at Richmond and waiting for a combat assignment,

my father was assigned as a depot test pilot, involved with flight-testing

recently-repaired aircraft that had been damaged. Not the safest job,

considering everything you’re flying had ben broken at some point. In one

letter home to his parents from this time, he signed off by saying “I have to

check out a P-39 this afternoon. Sure hope it holds together, those things are

hard to get out of.” Very reassuring to one’s mother, I’m sure.

So this one afternoon at the depot, Dad found himself in a Jug whose

cockpit suddenly filled with smoke. Fire! He had to bail out. But he didn’t see

a need to panic, since his feet weren’t in flames just yet. He took a moment to

aim the airplane out to sea so it wouldn’t crash on a civilian, and lock the

controls. Never having bailed out before, Dad didn’t know if he could manage to

jump far enough to clear the airplane’s tail. He decided to climb out onto the

wing, and work his way hand-over-hand along the leading edge out to the gun

barrels, clear of the tail, where he planned to let go and fall off. He got all

the way out there and happened to look back at the cockpit. The smoke had

stopped! Well, shame to waste a perfectly good airplane. He worked his way

back, and climbed back in. The fire was out, so he landed back at base. It

turned out to be nothing more than some smoldering wire insulation.

He was putting another of these patched-together Jugs through its paces

when half of the right wing broke off at the aileron/flap line! After a moment

of panic, he discovered it was still controllable as long as he kept it at full

throttle, but if he let go of the stick, or thrittled back, the unbroken wing

tried to flip the plane over. That also meant there was no way to bail out. So

he decided he’d try to fly it onto the runway, gear-up, at 400 mph. But you

still have to slow down at some point when you land. When he cut power at just

a few feet over the runway, the good wing took authority and the Jug

snap-rolled itself once (probably ripping the wing off), slammed down on its

belly, and careened down the runway (continuing to roll) shedding parts as it

went. The plane plowed through some boarding stairs (an image that stayed with

him!), passed under the nose of a parked C-47, and finally slammed nose-first

into an embankment. The only part of the airplane left was the cockpit and

engine, all in a sort of an accordion shape. Dad, displaying the luck that

would follow him throughout the war, was unhurt, though a bit hazey from

hitting his head on the gunsight. When people got to the crash site, Dad was a

bit delirious, busily flipping switches, trying to turn things off despite

there being nothing left on the other end of the switches. I have the top half

of the broken joystick grip from that plane.

|

Half a Jug grip. Click to enlarge. |

Dad's first combat duty, and his first kill, came during a one-month

volunteer stint chasing V-1 buzz-bombs over the English Channel. For this duty

he flew a P-47D bubbletop or possibly a P-47M, stripped of its armor and

carrying only two guns (the weight loss would allow a Thunderbolt to catch up

to the fast little missiles). Unfortunately I have no clue as to what unit he

was assigned to at the time.

While he was on patrol for V-1s, a Focke-Wulf 190 was impolite enough

to attack him. It took a few shots, missed, then the pilot decided to go home.

Well, you don’t shoot at my Dad and then say “never mind” and get off scott

free! During the maneuvering that followed, Dad got himself behind the German,

and fired. With only two of the Jug’s usual eight fifty-calibers, the Gereman

didn’t explode, but it was hit. The pilot veered off, headed for the deck, and

landed wheels-down in a field in northern France. Dad set up to strafe the

downed plane, but when the pilot didn't climb out, Dad, with the fearlessness (or

foolishness) that only being 21 can bring, landed his Jug next to the intact

enemy fighter, and ran up to meet his opponent face-to-face. But the pilot had

died of his wounds after he'd landed (perhaps fortunately for Dad). My father unbolted

the FW's joystick and took the pilot's headset as souvenirs. I still have the

joystick in my collection, though Dad sold the headset to a collector.

|

The joystick from the Fw-190. Click to enlarge. |

In September of 1944, Dad volunteered to help ferry a flight of thirty lend-lease Bell P-63 King Cobras destined for Russia, via Newfoundland, Iceland, France, and Sicily to Rome, where the Russian pilots would pick them up. In Lyon, France, the planes’ guns were armed up for the flight deeper into the Mediterranean. He said they saw 4 German fighters, but nobody was interested in a fight. According to one of his letters home, while in Italy, he "picked up" the top section of engine cowling from a crashed Italian Macchi 200 fighter. According to his campfire tales, he took part in shooting it down. This big hunk of metal now hangs in my basement. It’s riddled with bullet holes, but Dad says it's from when a bunch of GIs used the thing for target practice with their rifles. This story remains a mystery - did he shoot it down, or did he simply find it. I'll never know.

|

The cowl today. Click to enlarge. |

Dad was sent to Hawaii, where he guarded the islands

from such things as transports who forgot to turn on their IFF. If such a negligent thing

happened, he would fly up behind the airliner while it was still out to sea,

come up alongside so the pilots could see him, and tap his earphones in the

universal signal for “Turn your radio on, you idiot.” Then he’d slide back behind the wing

with his guns pointed, pointedly, at the engines. All he could usually see in

the airliner’s windows were lots of very large, round eyes.

While on Hawaii he also flew missions against Japanese paper balloons. These

balloons were hung with small incendiary bombs on timers to release them over

the western US, and sent aloft into the jetstream from Japan, with fingers

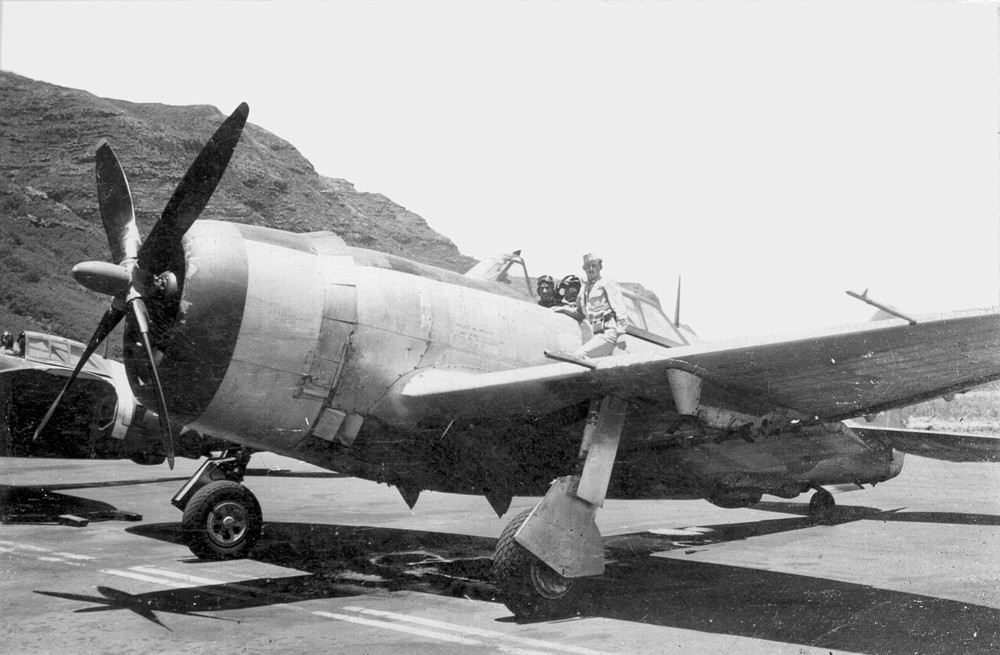

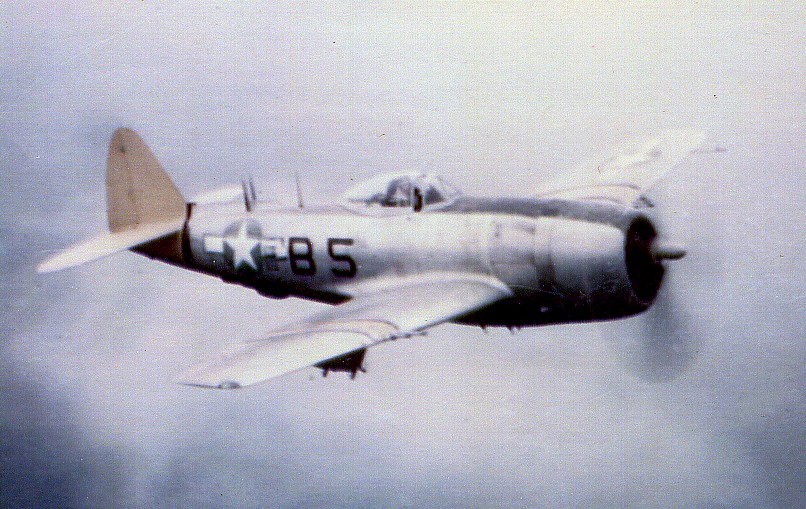

crossed. Using a silver razorbacked P-47D he'd named Jack the Ripper, again stripped down to two guns and no armor, Dad

would zoom-climb at the balloons, which floated far above the Thunderbolt's

maximum altitude. He'd hang on his prop as high as he could get the Jug to go,

then fire, and the recoil of the two .50s would stall the plane. He wasn’t

specific on how many he actually nailed.

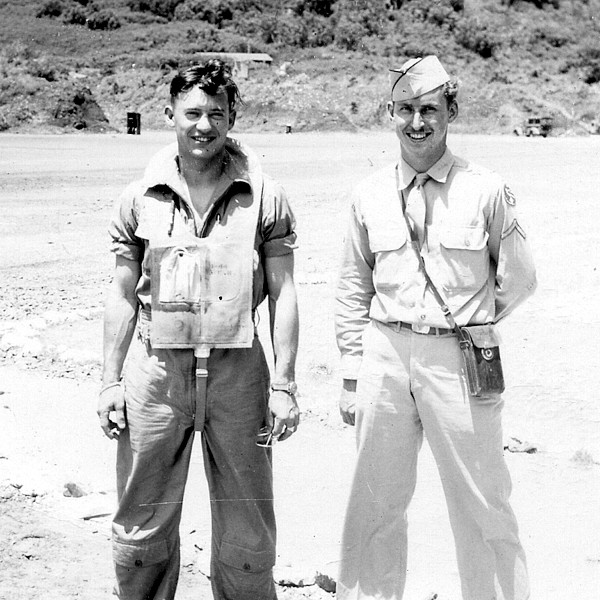

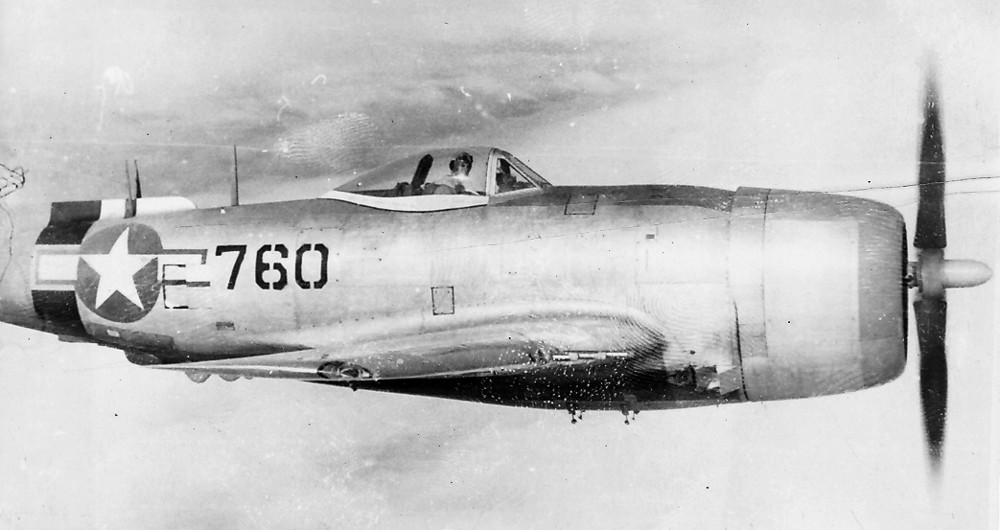

According to Dad's letters home from this time, he was assigned to the 508th Fighter Group, 468th Fighter Squadron. The background in the below pictures has been identified as Mokuleia Field on Hawaii.

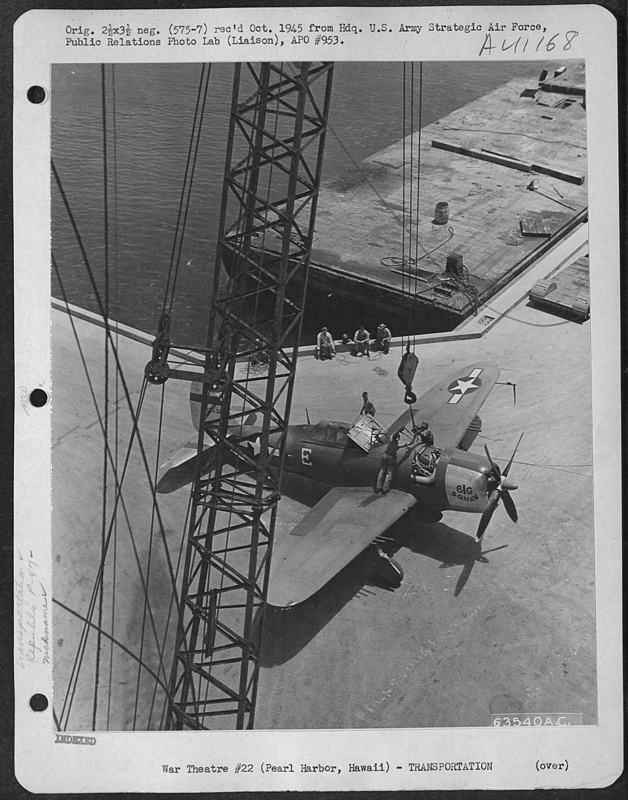

Dad was finally assigned to a regular combat unit, the 318th Fighter Group, 7th AF. The 318th was to take part in the invasion of Saipan, and the group was to be transported to the Marianas Islands by “Jeep” aircraft carriers. There was some question at first as to whether the P-47s should be landed aboard by their pilots, or hoisted aboard. So Dad, once again ignoring the rule "don't volunteer for anything," volunteered to try to land a Jug on the deck of a Long Island class escort carrier without benefit of arresting gear. He probably should have been clued in by the fact that they gave him an old war-weary plane to try it with. As he was on final, the stern of the ship dipped into a wave trough and the LSO waved him off. Never having seen a waveoff signal, Dad thought it meant "Cut power," which he did. Dad realized his mistake as he saw the ship pitching out from under him and applied throttle, but the Jug wouldn't respond and mushed along over the deck. As he passed the mid-point of the carrier, it reversed its pitching, its stern rose and its bow dipped out from under. Dad missed the ship altogether! The plane didn’t have enough oomph to stay in the air, so the only thing left to do was ditch rather unexpectedly into the sea ahead of the ship. Dad says that seeing a carrier coming at you at full speed, leaning hard over under full right rudder to try to miss you, is something you don't forget! A documentary I once saw on the Discovery Channel that included the Seventh Air Force's exploits in the Pacific showed the results of the test: P-47s of the 318th being hoisted aboard carriers by crane. I laughed out loud.

|

Big Squaw, a plane that Dad would later be assigned, being hoisted aboard a carrier at Pearl Harbor for the trip to Saipan. |

The 73rd and 19th squadrons went ashore on Saipan on 22 June, 1944. They launched from escort carriers (the only time P-47s ever did so) to the barely-captured Aslito Airfield, and immediately began ground attack operations. The 333rd squadron was held in reserve and it wasn't until 18 July that they catapult-launched from the escort carrier Sergent Bay. The 333rd began operations on 20 July. There is some question about what squadron Dad flew with at this time, because Dad is sure he went in on Saipan with the invasion force. In fact, he clearly remembers seeing an unusual-looking airplane diving on the beech nearby at roughly the same speed as him. He changed course to pull up alongside it to see what it was, and it turned out to be shell from a battleship’s main guns heading in! Dad quickly pulled away and went about his own business. He recalls flying Jack the Ripper at this time, but Ripper was not part of the 318th. He may have had another plane of the same name, or, hey it was a long time ago and hard to remember.

For details on Dad's planes, or at least what I can figure out, see my section of reasearch on Dad's planes.

Saipan was still basically an enemy-held island at the time, and the

group lived in their tents under constant sniper fire and air raids. Takeoffs

often took you directly over the enemy's guns. Life on Saipan, for the pilots,

included a certain amount of infantry fighting to defend the field, and Dad had

to use a Garand as well as a Thunderbolt. He has a few foxhole stories to go

with the flying stories. Once, for example, he had just gone down to the beach

after a battle to wash the dust off. There were still bodies floating in the

surf. Suddenly the jungle erupted with Japanese soldiers in a Banzai charge!

Dad dove into a foxhole (or shellhole) and started shooting. Another soldier jumped

in next to him also shooting at the enemy. When Dad saw it was a chaplain, he

exclaimed, “Father! What are you doing fighting?!” The chaplain answered, “Son,

God helps them that helps themselves!” leapt out of the hole and charged off

into the fray!

From Saipan Dad flew raids against nearby Japanese-held Tinian and Guam

in support of our troops trying to take those islands. Jack the Ripper (if indeed Dad was flying Ripper) ended

her service career ditched off Tinian's beach, the victim of ground fire. Dad

had to sit on the shore of the enemy held island while he waited for a landing

craft to pick him up.

When the Colonel was shot down on Tinian. Dad volunteered (there he

goes again) to go pick him up. He took an L-4 across the straights at wavetop

level, landed on the beech, the Colonel hopped in and they took off again.

Everybody started shooting at them at that point, and Dad spent the short trip

home slaloming around guysers of water thrown up by enemy shells.

Read Dad's personal account of that little adventure in "A Lament for the Cub".

The plane Dad was assigned next actually belonged to the 19th squadron

of the 318th, a P-47D-20-RA razorback, serial number 43-25327, named Big Squaw.

We assume Dad had been transferred to the 19th at this point, rather

than one squadron borrowing another’s aircraft. Big Squaw was apparently around

long enough to be well documented, for photos of her can be found in many books

about the 7th Air Force, though I can't swear that my father was in the cockpit

in any of them. Whoever may have flown her before, may father was her last

pilot, and Big Squaw ended up bellied-in on Saipan's beach.

|

A shot of Big Squaw on Saipan that I scanned from a book. Since Dad shared the plane, it may not be him in the cockpit. Click to enlarge. |

Once the Marianas Islands were secured, the 318th moved on to Ie Shima,

a tiny island off the northwest tip of Okinawa, at the end of April 1945. Dad

transitioned from razorbacks to a P-47N, which he named "Icky and Me"

because it was covered with mud when he got it.

What squadron Dad was with and when is somewhat confusing. Records do

show that Dad was assigned to the 333rd squadron on July 16, 1945.

I’m not sure what he was doing between the group’s move and his

reassignment. Presumeably he was still with the 19th.

For what few details I know about Icky, see (you guessed it) my section of reasearch on Dad's planes.

Living conditions were no better than Saipan, as Japanese soldiers

constantly waded across the shallow one mile wide channel from Okinawa to snipe

and raid.

From Ie, the 318th flew support missions for the 10th Army on Okinawa,

Very Long Range (VLR) fighter-bomber missions all the way to the main islands

of Japan itself, China, and as far north as Korea. They helped defend against

the Kamikaze attacks on our fleet off Okinawa, where Dad says he

got a couple. The 318th pioneered the use of napalm against entrenched troops

(and, in particluar, the characteristic womb-shaped burial chambers on Okinawa

which the Japanese hid in), and their P-47Ns were among the first to get

zero-length launch rails for five-inch rockets. Their specialty was the Very

Long Range strike mission, and their theme song, adapted from the “Joy Boys of

Radio” radio show, went something like this:

Very short theme song.

The missions were, as the old saw

goes, hours and hours of sheer boredom accented by thirty seconds of blind

panic.

Despite their good press, even P-47s didn't make it home all the time,

and Icky, torn up by flak over Japan, just gave up the ghost half way home from

one mission. Dad bailed out over open ocean and his wingman orbited overhead as

long as he could. In trining they were told, when you bail out over water, to

loosen your parachute harness when you get low over the water, and drop out of

the harness ten feet over the water. This lets the chute fall away from you so

it doesn’t cover you nad drown you. My father followed this advice, but the

distance to water is hard to judge without anything to provide scale. Dad

dropped out of his harness when he thought he was low enough – and fell (he

says) at least a hundred feet into the Pacific!

Dad figured he'd be found quickly enough since his wingman saw where he

fell, so he settled into his one-man life raft, ate his survival rations and

waited to be rescued.

He waited, and floated, for eight days.

During those eight days he learned a few things: you can't kill

seagulls with .45 shot shells; eating raw scorpion fish makes you sick as hell;

a one-man raft was no kind of boat to be in during a Pacific Ocean squall.

When a plane finally flew over, he didn't care who's it was, he just

flashed his signal mirror and hoped. Luckily it was a PBY. The crewman who

helped him aboard asked if he wanted to keep his life raft. Dad said,

"hell, no!" and emptied his .45 into it. I have his survival kit and

signal mirror, but we both wish he’d kept the raft as a souvenir.

When he got back he flew another P-47N, which he named Icky and Me once

again. This Icky survived the war to be sold to the Chinese Air Force, and Dad

remembers sadly watching her being flown off to her new home.

One of my favorite stories concerns a mission Dad wasn't supposed to

fly. He was due a day off, so he and his wingman, Hal Barbret, got royally

drunk at the nightly torpedo-juice party. Somehow they were assigned to fly a

two-plane flak suppression raid to a factory on Kyushu, which was scheduled to

be bombed by a B-25 unit later. On the long flight up to Japan they chatted

with each other constantly, forgetting the radio silence rule, and using call

signs such as "Shithead" and "Stupid." At the target, my

father, experienced at skip-bombing into railway tunnels (and narrowly missing

the mountain they were bored through), decided to try this precision technique

on the factory. Flying directly at the end of the building at exactly 16 feet

off the ground, he released one of his thousand-pound bombs, which skipped off

the pavement and went directly through the factory's main doors. What he didn't

consider was what would happen when you drop one half-ton bomb and leave the

other one on the opposite wing. Some hairy control inputs were required to keep

Icky from flipping over into the dirt, but Dad managed to keep level and pulled

up in time to see an explosion issue through the roof at the center of the

factory building. He came around again and deposited the other bomb in another

doorway. Barbret attempted the same single-bomb trick, also managing to live

through it. The two pilots buzzed around the target hitting anything that moved

until they suddenly realized that bombs were falling around them - the B-25s

had arrived, and Dad and 'Bret were under them! Upon landing back at Ie Shima,

they were chewed out and busted down to second louie for breaking radio silence

and acting like idiots. But when the day's mission was later analyzed it was

discovered that the two P-47Ns with four 1000 lb. bombs, twenty five-inch

rockets, sixteen machine guns and two drunk pilots did more damage to the

factory than the B-25s had. Their rank was restored.

One of the things Dad swears he destroyed on the ground during one of

these raids on Japan was an experimental Kikka jet fighter.

Oh, here’s a little triva: When you’re strafing, never fly below and

behind another P-47. His spent shells and links fall out of the bottom of his

wings and get sucked right into your own engine. Can cause problems if you want

to keep it running.

Dad wanted to fly anything he could, and World War Two gave him the

perfect opportunity. He flew the base's liquor supply run in a B-25, with cases

of beer slung in the bomb bay ready to drop if they got jumped; he ferried a

C-54 from Hawaii to Saipan without any 4-engine experience ("How hard can

it be?") and spent the whole flight wondering of the wings were supposed

to flex like that (a fighter’s wings don’t, but an airliner is designed to

flex); He piloted a B-17 with VIPs aboard and looped it at the General's

request; He even flew a C-46 over the Hump a few times. Of course, every chance

he got, he flew any fighter of any kind that was sitting around. For instance:

|

Margie, in all her bare-assed glory. Click to enlarge. |

Read Dad’s own account of the August 9th mission in his

story "Icky and Me".

My father scored nine Japanese kills during his Pacific career, but the

details are unclear. It happened in a very short hectic few months, from first

kill to end of hostilities. Dad wasn't taking notes, I guess, and his records

were lost long ago. He told me that if he'd known then that I'd want to know in

such detail, he'd have written it all down and taken more pictures, but he

really didn't care back then. He was having a hell of a lot of fun flying, and

just trying to get through it all alive. We don't know what types he shot down,

or when or where. One I know to be a zero which flew suddenly across his line

of sight, and disintegrated when Dad reflexively squeezed the trigger. He

swears he nailed a Tony just after it took off, but the gun camera film

couldn't prove it was airborne yet, so he was credited only with destroying it

on the ground. An Emily flying boat he attacked was credited as

"damaged" because it just wouldn't go down. Dad made several attack

runs and shot out two engines, but the big boat kept on cruising straight and

level and went off into a cloud.

Most of the 318th's work, though, was ground attack, and there are an

unknowable number of destroyed vehicles, buildings, ships, trains, parked airplanes,

artillery pieces and Japanese soldiers that fell to his Thunderbolt's eight

fifties, ten rockets, napalm and thousand-pound bombs. He was wounded twice:

once in the leg by shrapnel which required surgery to re-route an artery; and

he was hit in the stomach once by a rifle bullet that passed up through the

belly of his Jug, through the gas tanks and floor boards. While you can bet

both these incidents hurt, he seems to think getting malaria made him feel

worse than getting wounded.

Of interest, I think, was Dad's personal ordnance. When flying he

carried a Luger in a shoulder holster, and a Tommy gun fastened to one side of

the parachute harness with a fifty-round drum fastened to the other side. He

found the Luger after an encounter with a Japanese officer. Dad and a buddy

were walking along the beach one day when this officer, who'd been holing up in

a cave, tried to sneak up on them and kill them with his sword. They turned to see him

about to strike. Dad was quicker with his .45. They found his cave, and in it was a Luger and a case of ammo.

I still have the pistol, and although the bore is pretty rusty it still shoots

fine. And no, it's not a Nambu, it's a genuine Mauser-built German 9mm Luger.

With a little research I figured out it was one of 3000 shipped from Germany to

the Dutch East Indies, and taken when the Japanese captured that area.

My father’s stories, like anyone’s, go from funny to tragic. I can’t place all of them in a time frame. They could have happened on Saipan or Ie Shima. Here are a few combat shorts he told me:

There was a slit trench outside the tent area for diving into during air raids. Late one night, out of a sound sleep, Dad heard the blast of the nearby anti-aircraft gun firing. Air raid! Leaping out of bed, Dad dove for the slit trench … and landed in two feet of water. It wasn’t an air raid, and it wasn’t the gun firing. It was a tropical thunder storm.

Waking up on another night, Dad though he saw a Japanese soldier standing over his bunk! Reflexively grabbing his .45, he fired, nailing his hanging flight suit clean thru the armpit. I still have that flight jacket, with the hole. Lesson: wake up before you shoot.

After a mission, one of the pilots returned with damage. Whatever the damage was specifically, he couldn’t lower his landing gear, and he couldn’t drop his bombs. So he returned to base fully armed, and belly landed his P-47 on the abrasive coral runway (trivia: the coral wore out a set of tires after 8 landings). Dad watched, realizing that this damn fool was using a pair of 1,000 pound bombs as landing skids! Apparently the pilot hadn’t realized what he was doing, but halfway down the runway, he did. The guy leapt out of the plane before it stopped sliding, and, Dad says, to this day he’s never seen anyone run so fast.

The P-47 had no floor boards, per se, so if you dropped something, it went down into the belly of the plane. You could always tell, on long formation flights to Japan, when somebody dropped his pen. The plane would slide out of formation to a safe distance and roll upside down. The pilot could then pluck the pen off the canopy “over” his head, and get back in formation (rightside up, of course).

An unfortunate side effect of the way the Japanese fought was that you simply couldn’t trust a surrendering enemy. One day a ragged, exhausted-looking Japanese soldier approached Dad out of nowhere, with his hands clasped behind his head in the classic surrender pose. But our guys had been warned – the enemy sometimes held a grenade behind their heads and took you with them in a suicide attack. Dad unslung the Garand rifle he was carrying, pointed it at the Jap’s face, and gestured with the rifle, “Get your hands up where I can see them.” The man didn’t understand, and kept walking toward Dad and smiling. Dad kept gesturing and yelling, but the guy kept walking. So Dad shot him. You can imagine what a .30-06 to the face does. Sadly, the soldier didn’t have anything in his hands. Dad said he felt bad about that for a long time, but there was nothing else he could have done.

A Pacific typhoon passed over the island one day. Everyone was afraid the wind would damage the fighters. A loaded P-47N may weigh eleven tons, but it took off at 105 MPH, and a typhoon’s winds could reach those speeds. The solution they came up with was to tie the planes down facing into the wind, and have each pilot sit in his cockpit to work the rudder and keep the plane pointed the right way. When the storm came, the winds were strong enough for some of the pilots to “fly” their planes tied to the ground! Though the tie down cables kept the wheels down, they could lift their tails off the ground and keep the planes pointed into the wind.

I'm pretty sure this story happened on Ie Shima: One of my father’s squadronmates was a young guy named Danny. Danny was an exceptional musical talent, able to play any instrument after fooling around with it for just a little while. Dad and Danny became friends, and shared a tent at one point. One night there was an air raid. Apparently these had become old hat by this point, and Dad had stopped taking them seriously. You run to the ditch, it blows over, and you go back to your business. Hey, they were only 22 at the time, two young guys goofing around. They ran out of the tent, laughing, headed for the ditch. Dad realized he was barefoot, and yelled to Danny to wait while he ran back and got his boots. Danny turned to look at Dad, and a bullethole appeared squarely in the center of Danny’s forehead. Just that quick. Dad forgot about his boots and dove for the trench. That was the last time he saw Danny.

And this one I can place names and a date to: On July 31, 1945 on Ie Shima, There was a landing accident on the runway named Birch Strip that Dad witnessed. A P-47N flown by Lt. John Krieger finished its landing run and taxied off the end of the runway. But the Jug right behind, flown by Lt. Vaughn, overran Krieger's jug, and collided with it (whether it was brake failure, or simply the fact that it's impossible to see over the Thunderbolt's big nose while taxiing, I don't know). Vaughn’s 13-foot Curtiss propellor, with 2000 horsepower behind it, chewed a series of gouges up the length of the other plane’s fuselage. Sadly the last gouge was through the canopy, the cockpit, and the pilot. Dad had been watching the landings, and was the first person to jump up on the wing to see if he could help the pilot. Dad had known Krieger from around the east coast flying community. He’d even introduced him to his wife. The prop blade had cut Lt. Krieger wide open from shoulder to hip. He looked at Dad and said “Tell Mary I love her,” and died. There’s a short note in the back page of Dad’s logbook that simply says the date, and “John Krieger got killed today – overrun on landing, chopped up by prop.”

The Fog of War - There were a couple of incidents where the tunnel-vision of

concentrating on the moment came back to haunt Dad when the cold eye of the gun camera

film was reviewed later:

During one raid on Japan, taking "targets of opportunity," Dad was attacking

a barge chugging down a river in a port city. The barge happened to pass under a

roadway bridge, and Dad decided to simply keep the trigger pressed. The .50 calibers

might not go through the road, but in any case he kept his aiming point when the

barge reappeared, and he sank it. Unfortunately, when he and the squadron staff

reviewed his gun camera film back at Ie Shima, they could clearly see a civilian

woman get cut to pieces by his bullets. In his concentration of the moment, Dad

simply hadn't seen her.

It happened again after a strafing mission where the squadron blasted

some buildings at a Japanese target. Review of the gun camera footage showed,

much to Dad's surprise, that one of the "factory buildings" he'd srafed was a hospital

with a big red cross on the roof.

Oh, here’s an interesting little picture. This is an Okinawan family in their fishing boat. Nice shot, right? What’s so special? Dad says he took this picture from the cockpit of a P-47N, flying at wavetop level, with a Kodak Speed Graphic camera. Which means he needed two hands to work the camera, and was flying the plane with his knees. At an altitude of, what, twenty feet?

|

Wave "hi" from wave high. Click to enlarge. |

|

The surrender envoy taxying on Ie Shima. Click to enlarge. |

After hostilities ended, Dad stayed on Ie Shima and/or Okinawa for

about a year. He was apparently reassigned to a few different units and duties. For a time

he was with the 413th FG, and

I have a number of photos of him and Barbret in P-47Ns in that unit’s markings.

Among his photos is also a picture of an arched gateway bearing the name of the

34th FS (413th FG), and a color picture of him flying in

a Jug in 34th FS markings (taken by Barbret).

Dad transitioned to B-29s for a while and spent some time instructing

new B-29 pilots. His log book notes his first transition flight in a B-29 as December 31, 1945. He once had to land a B-29 with its nose wheel jammed up, and

spontaneously converted it to a tail-dragger by having the whole crew run into

the tail. Once it was down and had slowed down enough, he had everybody run

forward so he could set the nose down.

He excercised his other skills by serving as a carpenter, a machinist,

and a photographer. He built himself an easy chair to make life in his tent

more comfortable. Not content to do it like everyone else, he built an ash tray

into one arm of the chair, and a working radio into the other!

He shared a tent with Barbret, and they got matching Harleys to tool

around on.

Everybody needs a mascot, so they domesticated one of the local rhesus monkeys and named him

Turbo.

Dad got his first ride in one of them new-fangled whirlybirds on Okinawa,

when some of the guys took a Sikorsky R-4 helicopter up to the north end of the

island to hunt wild pigs.

There were still Japanese POWs on the island, and each pilot was

assigned to supervise three of them. While serving as the foreman of a base

machine shop, with three very cooperative prisoners under his watch, another

prisoner suddenly decided the war wasn’t over enough for him. Dad saw the man

about to club another pilot with a piece of steel at the next machine station.

A couple of years of war had Dad’s reflexes plenty sharp, and he had his Luger

out and a bullet through the prisoner’s brain before he could bring the

makeshift club down.

As for Dad's guys being polite - who could blame them?! They saw what

happens when you piss him off!

That wasn’t the only exercise the Luger got. I’m unclear if this event

happened during hostilities or after the war had ended (I think it was after):

an American soldier who had gone nuts was being escorted to the lockup when he

broke free. He killed or knocked out his MPs, and was standing there shooting

randomly around with a .30 caliber carbine. Dad happened to be passing on his

Harley when a bullet zinged off the bike. Dad reflexively dumped the bike and

got down behind it. Seeing the situation, he returned fire with the Luger. He

claims to have put five shots into the man’s chest, but the guy was very big,

and the shots didn’t move him. But they did the trick, and the man finally

dropped, dead.

Speaking of that Harley, one interesting thing Dad accomplished during

this time was to establish the local motorcycle speed record for a bored

fighter pilot 5000 miles from home: 180 mph down the runway at Kadena Field on Okinawa.

He decided to slow down because the front tire was spinning so fast it was

coming to a point at the middle from centrifugal force!

Apparently there was a parade on Okinawa at some point. Dad never mentioned why

that I recall, but he designed a float for a P-47 unit. It was a cartoon P-47 with a

cartoon pilot. The "Jug Junior" was built in classic model plane former-and-stringer fashion

and had a working gasoline engine in it. The sign held up by the two enlisted men in

the photo makes it clear the float was for the 301st fighter Wing, but I can find no

references at all for this unit existing. Yet another Mystery!

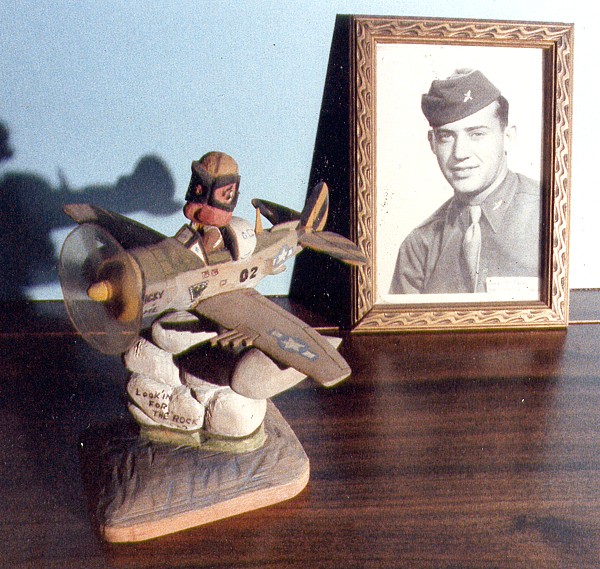

I don't know which came first, but Dad carved a small version of this cartoon

from balsa wood and sent it him to his mother. It's titled "Lookin' for the Rock," and

depicts him in Icky and Me trying to find Ie Shima under the clouds. It currently resides

in my sister's collection.

My father’s last military entry in his flight log was five landings in

a B-29 on March 25, 1946 on Okinawa. It’s frustrating that, for some reason,

all the pages that might have combat time listed – from April 1945 to late October,

are missing. I don’t know if Army censors removed them or what.

On his way home on the troop ship, my father suddenly decided he was tired of carrying

his trunk around, so he tossed it overboard. And took a picture of it. I've often wondered what

treasures he threw away that I wish I had now - photos, records, souvenirs. Or just

clothes? I'll never know. I'm also a bit ticked off that he took a picture of a sinking

trunk, but never any of the planes he flew in combat! Priorities, Dad, prioroties!

But he still managed to bring home a bunch of souvenirs which have languished in various china cabinets, boxes and shelves over the years. Here are a few of the more interesting pieces in my collection (besides the FW Joystick and the Macchi cowl):

(1) His last issued flying helmet (with his name and S/N stamped inside)

(2) The cockpit compass salvaged from a Mitsubishi J2M Raiden ("Jack") that crashed on the beach at Okinawa

(3) An altimeter from god knows what and where

(4) A reflector gunsight that Dad said was from a P-40

(5) The very mirror Dad used to signal that PBY that picked him up out of the ocean

(6) Dad's dogtags

(7) An assortment of flying maps of the Pacific printed on silk

(8) Flexible plastic waterproof holster

(9) Combat knife

(10) A couple of bills of military scrip (occupation money?), 10 sen denomination

(11) Computer; Dead Reckoning, Type AN 5835-1

(12) A 5" folding knife/saw from his bailout survival pack

Background: A silk flying map for "Japan and South China Seas, No. C-52"

Gram saved all his letters home. He wrote almost daily from training, but rarely during deployment. So once again we seem to have almost no written record of his days in combat, even from Dad himself. Frustrating for historian lurking in me.

Back home after the war, Dad

worked briefly for Republic Aviation in Farmingdale, Long Island, as a test

pilot. He flew aileron flutter tests on the XF-84, which he unfortunately rolled

up into a ball on landing. He left Republic after receiving a back injury in

the crash. He didn’t seem to want to talk much more about that chapter in his

career, so that’s all I know about it.

After the war, Dad got one more chance to buzz the house with a fighter. Some people at local Teterboro airport were converting a P-38 to a racing plane by replacing the Allisons with a pair of Roll Royce Merlins. They needed a test pilot, and Dad happened to be the only handy guy with P-38 time. With the throttles wide open he did a balls-out run along the treetops in Franklin Lakes, skimmed our roof and pulled up to head back to the airport. Once cruising, he was shocked to notice both engine cowlings were loose and rattling. He took it easy on the way back, and after landing found that torque from the more-powerful Merlins had actually twisted the stock engine mounts. Oops. He assumed a dignified test pilot attitude, recommended they build sturdier mounts, and fled before they started blaming it on him.

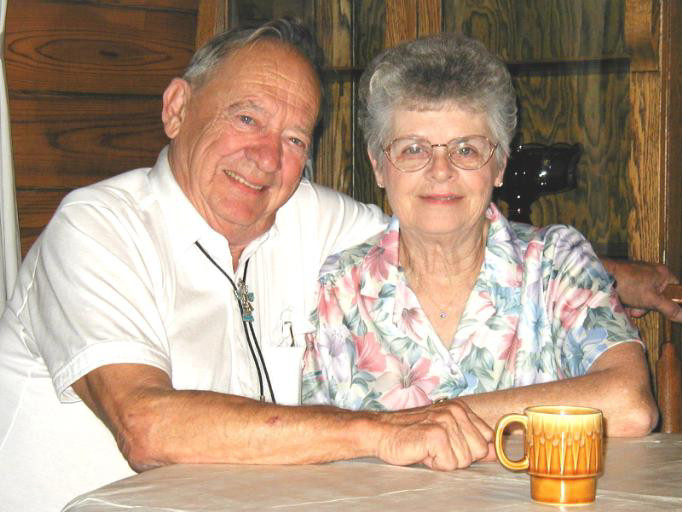

While working as a window trimmer at W.T. Grant's department store in

Hackensack, NJ, Jack Payne met a winsom young cashier from Dumont named Gladys Reed.

They got married in 1949. All through the war Dad had been sending money home to

his parents, and Gram gave it all back to him. Eventually (about 1953) he used it to buy a

Taylorcraft (NC36102). After a while he sold the Taylorcraft and got his dream plane, a 1939 Piper J-3

Cub (N27026) (first flight logged on 9/29/59). With that little blue Cub, he

started an aerial photography business with a friend, Paul Neilson, called

Sylvania Air Photo, based at Lincoln Park Airport (New Jersey). Remember that

Focke Wulf he shot down over France? Just for the hell of it, he mounted the

souvenir joystick in the Cub’s front office.

Probably Dad’s last chance to fly a fighter happened in the 1950s. He

got a call from someone at Lincoln Park. Some young guys had bought a surplus

P-51 Mustang to fix up, but they’d had engine trouble and landed it on a short

road in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. The road was too short for the pilot, who

had little Mustang time, but everyone at Lincoln Park knew Dad had flown off short

runways in the war. If they couldn’t get the plane flown out, they’d have to

take it apart and truck it.

Sizing up the runway, Dad knew he could do it. There was more runway

than at Ie Shima, and a lighter airplane. He ran the engine up with the brakes

locked to keep acceleration time short, released the brakes, and was off the

ground in plenty of time. But he wanted to make sure he had enough airspeed to

maneuver, so he raised the landing gear and kept it right on the deck, aiming

straight at the tall trees at the end of the road. At the last moment, he

pulled up easily, flew it to Lincoln Park, and hopped out.

When the owners finally got there, they screamed at him, called him all

sorts of nasty names and questioned his abilites. They thought he’d almost hit

the trees out of stupidity, rather than just being a hot dog. Some days you

just can’t win.

Sadly, The Cub was wrecked in the closing hours of 1961 when a

new-year's eve wind storm ripped her out of her tie-downs and flipped her over

into a drainage ditch. We took her mangled wings off, towed her home and stuck

her in the garage. I used to sit in her pilot’s seat, surrounded by open

framework, and pretend. Dad eventually sold the remains, and we understand she

was rebuilt and may - who knows - still be flying somewhere. I was so young I can barely

remember flying in her, but I do vaguely recall one flight sitting up front,

barely able to see out, and dad saying “you got the controls!” (well, for about

a minute anyway). Dad kept a torn piece of the fuselage fabric with the word

“PHOTO” on it, and the broken prop, and I have them now. It was nice having an

actual color sample to build a model from.

Once again, you can see more details on the Cub in my section of reasearch on Dad's planes.

After the Cub passed on, Dad stopped flying regularly and settled down into a long career as a machinist, a trade he’d always enjoyed. So much so that he had his own machine shop in the basement, and took in machining work in his spare time. He always had a project of some kind going, from designing boats (the Punkin Seed class sailboat, and redwood strip canoe sold through Popular Science magazine) to brass model steam engines and kooky weather vanes. He and mom retired to a beautiful little log cabin (that he designed himself) on a huge property in New York state. They lived there for 14 years, and then moved to South Carolina to spend time with my sister Lynn and her kids and their families.

No boy could have had a better role model growing up. One of the guidelines I've always used for my decisions and behavior in life, and still do, is to do nothing that Dad would find fault with. He once told me "All I can pass on to you is my good name. Don't screw it up!" Best advice a father can give.

He was my dad, and he was my hero.